Author’s note: This article came about thanks to an in-depth discussion with my fellow Indonesian Substack-writer. If you like this blog, check out his work at.

As a bilingual in both Indonesian (AKA Bahasa) and English, I can’t help but make comparisons between the two languages. I think it’s something that’s inevitable for any bilingual person. Such a comparison will be the basis of this blogpost.

But before I begin, I would like to give this caveat:

I am not a linguist nor am I an expert in languages. My undergraduate degree is in history and political science while my graduate degree is in management. Meanwhile, the bulk of my work experience is in security. I’ve also done some food deliveries for some extra cash. Currently, I write fiction, reviews, articles, and blogposts in my spare time. I may be a polymath, but linguistics ain’t part of my expertise.

With all that out of the way, I will risk being called a fraud and give my $0.02 on this subject.

Syllables

First, I would like to begin with the one aspect that’s the clearest to me and those who are bilingual in both languages: the syllables. I said before that “English is an objectively easier language to use than Indonesian, and I don’t mean easier to learn.” The reason I said this is because of how many syllables can be found in either language.

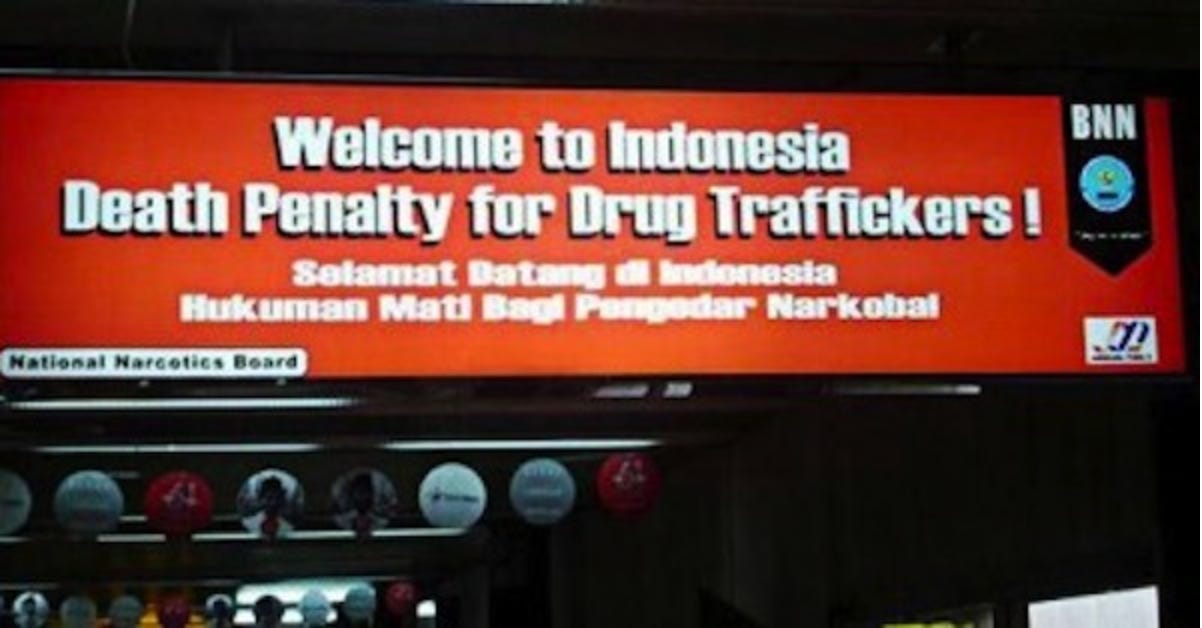

As an example, I would like to use the sign in above picture. In English, the sign says: “Welcome to Indonesia. Death penalty to drug traffickers.” That’s 16 syllables in total. In Indonesian: “Selamat datang di Indonesia. Hukuman mati bagi pengedar narkoba.” That’s 23 syllables, seven more syllables than the English one.

This means that this particular Indonesian sentence is 43.75% longer than its English counterpart.

Yes, I calculated that.

But why does this matter? …I’ll tell you!

I can’t speak for other bilinguals of English and Indonesian, but I personally find Indonesian to be somewhat clunky at times. It’s not the most efficient language to use. This makes sense, English had been used as a “trade” language for centuries. Not only is English the lingua franca of the world, it had also been the language of two world-spanning empires (the British and the American).

But English is not just more efficient than Indonesian. In many ways, it’s also more beautiful.

Pronouns and Tenses

This is where I’ll jump into some dangerous territory, but it’s too late to turn back now. I believe that one of the best aspects of the English language is its gendered-pronouns. Some may think that he and she (and it) of English as compared to the dia of Indonesian are not worth talking about.

They are wrong.

There’s a reason why gendered pronouns had been a subject of intense culture wars in the West for the last few years, if not decades (though that’s a story for another post). One result of this in the English language is the popularization of the singular they.

I can’t tell you enough how much I despise the “singular they”. No, it’s not that it’s “bad grammar” (though it is). My issue is that it destroyed an important aspect of the English language.

I’ve seen defenders of ‘singular they’ claim that it had been used for centuries. I am skeptical of that claim, but it’s irrelevant even if true. The issue isn’t that no one had ever used “gender-neutral pronouns” before. The issue is that gender-based pronouns are objectively good and undermining them will leave a language worse off.

One objection to this is the issue of using a singular for something that can be male or female. The solution is to use the masculine pronouns - which was (and is) the practice for centuries.

This is where I get to the Indonesian language (finally!). As I implied before, Indonesian has no gendered pronouns. Remember when I said that Indonesian is a clunky language? Well, this is one of the reasons why. If one wants to be specific in a sentence, the option to use he or she or it to distinguish the subjects is simply not there.

And this hurts the language.

Moving on to a less controversial subject, I want to briefly talk about the tenses in the English language. As speakers of Indonesian know, the language doesn’t have grammatical tenses. This means that we don’t use specialized words to indicate when an action is happening (past, present, future, etc.).

This may not seem like a big deal on the surface. But as a fiction writer, I find this aspect of the English language to be significant. When I write my stories, I use past tense (like most writers). Very rarely do I see a story written in present tense and when it does, it just feels different.

What’s the implication? … Honestly, I don’t know. But I thought it’s something interesting to point out.

English in my Indonesian

Readers may surmise that the general bent of this blogpost is that Indonesian is a clunkier language than English. And they would be right.

My hypothesis is that the general clunkiness of the Indonesian language is one of the reasons why Indonesian speakers like to use English words in their prose.

Just take a look at this particular passage from Dari Imamat Parmalim ke Imamat Katolik (I made a review of this book in a previous blogpost):

To be fair, this is not all that different to how English speakers would use Latin or French words. But I do notice that whenever there is an English word in an Indonesian prose, it would serve to quicken the pace of the sentence. Meanwhile, French and Latin words don’t really do that for an English prose; sometimes they may even slow down the pace. This phenomenon is a little hard to describe, it’s something that one has to read for himself.

Conclusion

People might get the impression that I think the English language should replace the Indonesian. But that’s just wrong. In fact, as I’ve described in an earlier blogpost, I want to re-learn (so to speak) the mother tongue that I’m slowly losing.

However, I need to be honest. There are aspects of the Indonesian language that I found to be lacking compared to English. I can’t stress enough how wooden and clunky it is.

I believe that the reason for this is because the Indonesian language as we know it is a relatively young language. “Bahasa Indonesia” became the country’s national language after it had achieved independence from the Dutch colonial government. Prior to independence, most people speak their local languages such as Javanese. Even to this day, most people have their local languages/dialects as their first language instead of Bahasa Indonesia. Meanwhile, the official language of the country prior to independence was Dutch.

Some may argue that the Indonesian language was older, that it had been used as a lingua franca of the country for five hundred years or so. I beg to differ, that language is Malay. Yes, Indonesian is based on Malay. But the language as it is now dates back to the Indonesian National Revolution when the Indonesians decided to simplify the existing Malay and use the resulting product as the country’s national language.

But this doesn’t mean the Indonesian language is doomed to be a clunky and overly simple language until kingdom come. People who speak Indonesian as a native language will doubtless know that there are actually two Indonesian languages: the slang and the formal. To me, the slang variant of Indonesian always feels more natural and flows better than formal Indonesian.

Perhaps this is where the Indonesian language will go next. And perhaps the English language will play a part in it just as French and Latin had played a part in the development of the English language from its Germanic roots.

Until next time,

Michael P. Marpaung

Thanks for reading. Please like, subscribe, and leave a comment.

If you like this blogpost, check out my fiction-based works at Germanicus Publishing:

This reminds me of the Philippines. Tagalog is the national language and my wifes* local dialect is Bisaya or Cebuano or Visayas--different names for the same language. It has no pronouns, and she still mixes up pronouns today.

I understand linguistically the dialects of the philippines represent a blend from taiwan and from indonesia/new guinea, so there might be some etymological overlap. There’s also extensive english mixed into daily use and spanish loanwords.

I would say in the Philippines the languages are very prefix oriented and use a lot of marker words which have no translation in english.

Ng Prutas = the fruit

Mga Prutas = the fruits.

The concept english demonstrates with an “s” has its own word in the Philippines.

Very interesting stuff. I love languages so I appreciated learning about yours and seeing some similarities between it and the Philippines!

Thank you!

From the other side of it, learning Indonesian enough to function day in and day out was easy. Comprehending Indonesians speaking to each other was another thing altogether. Easier on Sumatra with more consistently Malay-based slang. On Java, no way. Too much Javanese mixed in.