No Man Was More Justly Hanged Than Dietrich Bonhoeffer?

A reflection on a film review by Dr. E. Michael Jones.

Napoleon Bonaparte once said that ‘history is written by the winners’. I opened with this because the topic of this blogpost concerns a figure whom for so long I had accepted as a quasi-saint without a second thought: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran pastor executed by Nazi Germany in the waning days of World War II.

When Dr. E. Michael Jones of Culture Wars magazine said on his podcast that “no man was more justly hanged than Dietrich Bonhoeffer”, I had to do a double take. Really?

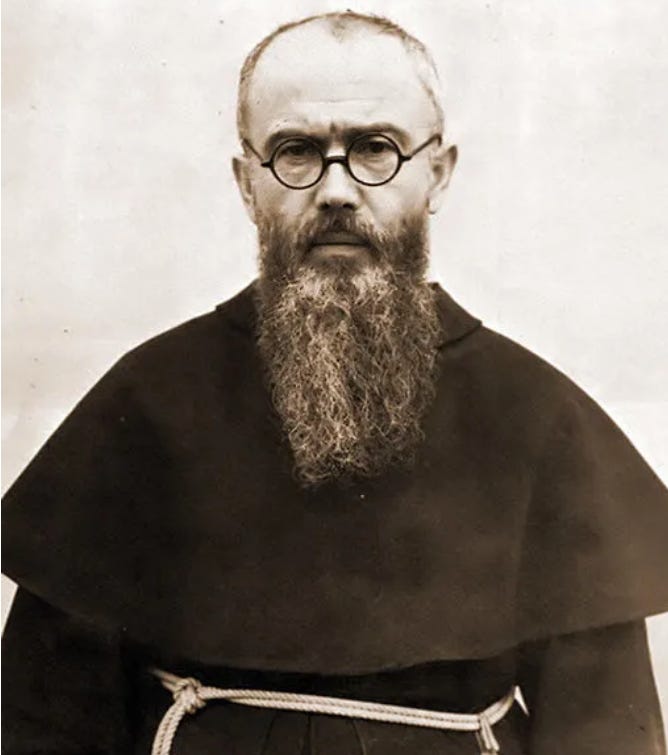

Personally, I never looked too deeply into the life of Pastor Bonhoeffer other than that he opposed the Nazis who eventually killed him in a concentration camp. I thought he was the protestant version of St. Maximilian Kolbe. That was as far as I thought of the guy.

Boy had I been missing out.

Pastor Bonhoeffer

In the January 2025 issue of Culture Wars, Dr. Jones followed up on his remark in his review of the movie Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin produced by Angel Studios (the studio known for high profile Christian/conservative productions like The Chosen and Sound of Freedom) and directed by Todd Komarnicki.

For those unfamiliar with the magazine, this isn’t the usual kind of reviews which delved into the cinematography of the movie. Rather, as the magazine’s name suggests, the reviews of Culture Wars look into the cultural implications of the movies and books it reviewed.

First, let’s get into the subtitle of the movie: pastor, spy… assassin?

You Say You Want a Revolution

That’s right, Pastor Bonhoeffer was actually involved in the assassination plot of Adolf Hitler, the infamous 20 July plot (AKA Operation Valkyrie). Did you know that? I didn’t.

Had I known of this fact about Pastor Bonhoeffer, I would have thought much differently about the man. Now I know what some of you might be thinking: “But Michael, he wanted to kill Adolf Hitler! Hitler!” Now hold that thought, I’ll get into that.

Now to be fair, it’s still debatable how deeply Pastor Bonhoeffer was involved in that plot. Or whether or not he actually took part. That said, he was most likely aware of it and would have approved given his strong opposition to the Nazi regime, so strong that he was put to death just two months before the end of the war.

Unfortunately for me, Wikipedia was very vague about Bonhoeffer’s possible involvement in that plot:

Going back to the movie, Jones’ review was where he made the logical connections that he is known for. As it turns out, Komarnicki’s movie is as much about the United States as it is about Germany.

This was clear when we looked into Jones’ bold declaration; it was actually a variation of a famous saying by American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne regarding John Brown: “nobody was ever more justly hanged”.

For those of you non-Americans (and lot of Americans too, let’s be honest) who didn’t know who John Brown was, he was a militant abolitionist. Unlike many abolitionists who worked peacefully to end slavery in the United States, Brown instead tried to incite a slave revolt in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia thanks to American Civil War politics).

You might think, ‘well what’s so bad about that?” My response is that revolts are never pretty, especially slave revolts. Just look at Haiti.

Keep in mind that Hawthorne was pro-abolitionist. Yet he was of the opinion that John Brown was not only wrong, but he deserved to be executed.

Today, the American mind struggled to comprehend Hawthorne’s position because they’ve completely internalized the proposition that the correct ideology justifies anything.

Of course, they wouldn’t put it that way. They’ll try to be religious about it, at least the right-wing ones, whom I consider to be the true holders of American identity. The left, with their persistent admiration for Europe and Canada at the expense of their own country and their inability to sympathize with the plight of their own countrymen as opposed to people in the Global South, hate American identity for reasons I will not get into. Going back to the right… if you spend enough time in American right-wing/conservative circles, you’ll run into their type. The “Bible and gun” folks.

Like John Brown…

Now let’s go to Jones’ review itself. But before we get into the issue of tyrannicide, let’s return to the man himself, Pastor Bonhoeffer.

Jones, Metaxas, and Bonhoeffer

Before we begin… I will not get into too much detail on Jones’ review because I think you should check it out for yourself. Here’s the link. At the moment, you can get the digital magazine for just US$4, not even the price of a cup of coffee (unless you live in Indonesia like me).

Moving on…

In his review of Komarnicki’s movie, Jones spent much ink delving into the works of Eric Metaxas, a prominent American conservative figure, and his book, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. The fact that the name of that book sounds suspiciously similar to Komarnicki’s movie is easily explained: the movie was based on the book.

Thus, the similarity of titles was not a coincidence. Neither was the hagiographic treatment given to the late Bonhoeffer both by the movie and Metaxas’ book.

Now Jones was no stranger to controversial opinions, and this review was no different. As a Catholic, he clearly resented the attempts by Metaxas and Angel Studios to portray Bonhoeffer as a sort of ‘protestant saint’. But that was not all. Jones also delved into Protestantism’s failing struggle to resist the racial ideology of Adolf Hitler. To quote (p. 43):

Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 created a crisis for the Lutheran state church when he imposed racial criteria for church membership. Lutherans had never hammered out the boundaries between the church and the state as the Catholic Church had by articulating the relationship between the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and the pope who was the sovereign over the Roman Catholic Church. The unresolved relationship between the Lutheran church and the German state became an unavoidable crisis when the church adopted the Nuremberg racial laws, making their separation from any notion of a universal church impossible to ignore.

But why did Jones resist the campaign to “sanctify” Bonhoeffer? Tyrannicide. We live in a world informed by movies like Star Wars where rebellion is seen as an absolute good. The West as we know it had their founding myths in events like the American Revolution; even the Global South had the wars of independence against colonial powers (like my country Indonesia and her fight against the Dutch colonial government). Thus, we have taken for granted the idea that we can kill our political leaders if they are being tyrannical… or if we are upset enough at them.

Yet that was not the original understanding of tyrannicide which Jones painstakingly provided the reader. The classical era saw diverse opinions regarding the morality of tyrannicide - from Plato who saw it as licit to Aristotle who saw it as a cynical power grab by those who would undertake it. As for the Catholic thinkers, there was St. Thomas Aquinas who held that a person may resist a tyrant if he ordered to do something immoral; yet the Angelic Doctor believed that a person of a lower social status should not take the life of a prince, even a tyrant.

To summarize, both classical and medieval Catholic thinkers thought poorly of tyrannicide. Yet that consensus changed thanks to the Protestant Reformation. The leaders of the Reformation, seeing themselves as scrappy rebels against the authority of the Catholic Church, opened the door to tyrannicide through John Calvin. On the other side, Puritan tyranny in England and Ireland under Oliver Cromwell led the Catholics to rethink their position on tyrannicide.

From there, centuries later, we got to Dietrich Bonhoeffer now living under the tyranny of National Socialism. What was he supposed to do? That dilemma led him to seek out likeminded allies who eventually conspired to murder Hitler.

Jones argued that Bonhoeffer’s Protestantism had intellectually crippled him in discerning what would be his best course of action given his situation.

Yet on the other side of the coin, Bonhoeffer also had a complicated relationship with the Catholic Church. Like many protestants before (and after) him, he felt the attractive pull of Catholicism. For Bonhoeffer, said attraction was in the Church’s ability to transcend race and nationality. To quote (p. 40):

Bonhoeffer also found the Catholic Church’s “transcendence of race and national identity” especially attractive in contrast to the ethnocentrism which the Lutheran Church in Germany had always exhibited and which it was now experiencing in a particularly virulent form as it welcomed with open arms the emergence of Aryan Christianity. After attending Mass on Palm Sunday, Bonhoeffer wrote that it was “the first day that something of the reality of Catholicism dawned on me, nothing romantic or the like, but rather that I am beginning, I believe, to understand the concept ‘church’”.

Yet despite this high praise, Bonhoeffer never made the jump to Rome. Why was that? Jones’ answer was simple: ethnocentrism.

Coda

Jones’ review was a very exhaustive dive into the life and theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. As Jones was a Catholic, an unapologetic one at that, he was not afraid to voice his criticisms of Protestant leaders and thought. Yet Jones was also fair. For example, Jones acknowledged that the leader of the 20 July plot, Claus von Stauffenberg, was a Catholic. Jones argued that Stauffenberg’s Catholicism was nominal at best and that he himself was infected by the same ethnocentrism that gripped Bonhoeffer. I don’t know how true that is; for now, I’ll take Jones’ word for it.

Then we get to the crux of the issue; why it’s very difficult to have a rational conversation about this topic, and why Bonhoeffer is being held in high regard by many:

What about Hitler?

What about him? I don’t disagree that he and his regime had done evil things. Yet as Jones pointed out in his review, Hitler was not just the leader of Germany. He was also the leader of Germany at the time when the country was in the middle of an existential battle against the communist Soviet Union, led by an arguably worse leader in Joseph Stalin.

Was Adolf Hitler such a figure of evil that it warranted tyrannicide? Jones, for his part, disagreed (p. 46):

The physician who presided over Bonhoeffer’s death claimed that he had “seen a man die so entirely submissive to the will of God”. Komarnicki does his best to create that impression at the end of the film by having Bonhoeffer preside at an impromptu and improbable Eucharistic celebration, but we remain unconvinced and claim that no man was more justly hanged1.

Source

Jones, E. M., et al. Culture Wars, Volume 44, Issue 2. https://culturewars.com/volumes-41-50/culture-wars-volume-44-issue-2

Emphasis mine.

Setting aside everything else, it's a bit inaccurate to say that Germany was "in the middle of an existential battle" with the Soviet Union without acknowledging that Hitler and the USSR had a non-aggression pact signed August 1939 (under which they carved up eastern Europe) and which Nazi Germany then violated by attacking the Soviets in 1941 after Stalin had somewhat stupidly stood by as everyone else was cleared off the board. The Soviet Union was horrific, yes, but come on. The Nazis were a whole different level of evil. Did the review mention the Holocaust, or dare I ask?